International carbon markets are entering a decisive phase of clarification. Long shaped by a wide range of approaches and uses, they are now being pulled toward higher expectations of consistency, transparency and traceability. In this context, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement stands out as a structuring text: beyond its technical nature, it frames international cooperation on carbon mechanisms and places accounting integrity at the core of the system, notably to prevent double counting of emission reductions. For companies and investors, the stakes are immediate. Article 6—and in particular its 6.4 mechanism—could accelerate the structuring of international carbon markets around more harmonised rules, while raising the bar on evidence, governance and reporting. Reforest’Action’s expertise is grounded in a demanding reading of Article 6, with the aim of shedding light on this evolving framework and its implications for economic actors.

Article 6 within the architecture of the Paris Agreement

A historic agreement, now a framework for action

Ten years after its adoption, the Paris Agreement is no longer merely a diplomatic horizon: it is increasingly shaping the transformation pathway of economies. Its architecture is built on a fundamental principle: each country defines a national contribution to the collective effort—its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC)—and reports regularly on progress. In other words, climate action becomes a matter of public steering: measured, compared, reviewed, and designed to increase in ambition over successive cycles.

The distinctive role of Article 6

Within this architecture, Article 6 occupies a particular place. It enables countries to cooperate voluntarily in order to meet their climate objectives and enhance overall ambition, notably through market-based approaches. It also introduces a requirement that changes the game: accounting integrity, understood as the ability to track, allocate and prevent double counting of emission reductions. When mitigation outcomes are transferred from one country to another, the logic of the Paris Agreement requires that the same tonne of CO₂ not be counted twice in two different places. Article 6 therefore frames these transfers and предусматривает the use of corresponding adjustments, designed to preserve the consistency of national accounts when units are transferred—particularly under Article 6.2 (transfers between two countries).

Toward a more institutionalised market

This marks a clear shift in paradigm. Carbon markets—long perceived as a heterogeneous landscape that can be difficult to navigate—are progressively moving toward a more institutionalised and more tightly framed system, where credibility depends as much on the quality of projects as on the accounting, traceability and reporting rules that surround units. This is precisely why Article 6 has become a central topic for economic actors. Beneath the surface, the debate is evolving: the question is no longer only about acquiring “high-quality” credits, but about credits embedded in an increasingly structured climate accounting system at both national and international levels.

Three cooperation pathways in support of climate objectives

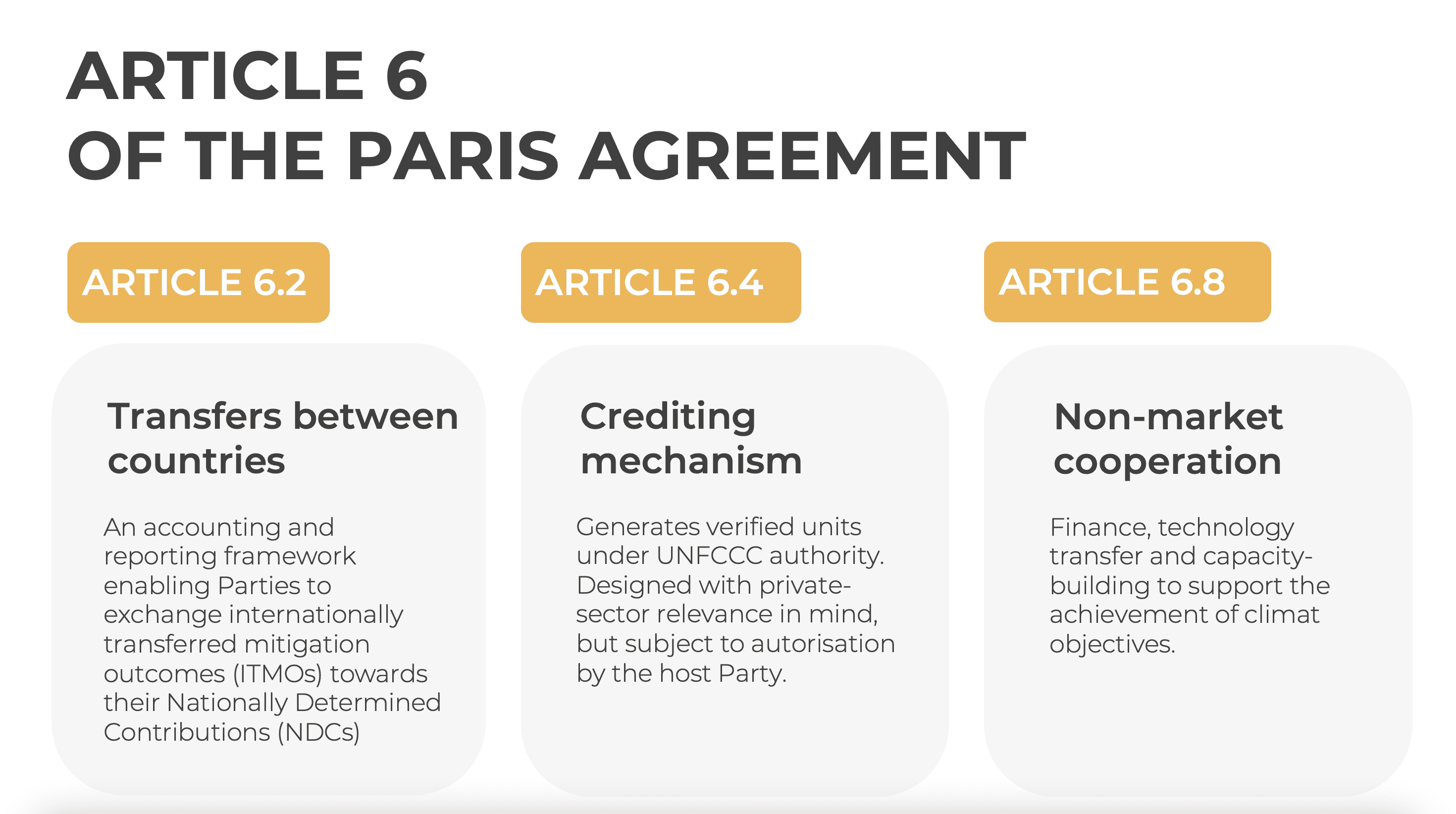

Cooperation between countries under Article 6 can take three forms, commonly referred to by their respective paragraphs: 6.2, 6.4 and 6.8—while the other paragraphs primarily set out the principles, requirements and cross-cutting modalities of the framework. The UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) presents these as the three components of Article 6: an accounting framework for international transfers (6.2), a central crediting mechanism under UN supervision (6.4), and a channel for non-market cooperation (6.8). While Article 6 covers all forms of cooperation between countries in support of their climate targets—and is therefore not limited to carbon markets—these markets remain among its most visible and most structuring expressions for economic actors.

The three pillars of Article 6

Article 6.2: transfers between countries

The first pillar, Article 6.2, governs “cooperative approaches” that allow countries to use internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) toward their NDCs. This is where a logic of intergovernmental exchanges emerges: a country that overachieves on its targets may transfer part of those outcomes to another country. In practice, this enables bilateral or plurilateral cooperation, with requirements on monitoring, transparency and accounting consistency. The UNFCCC describes this pillar as an accounting and reporting guidance framework governing the use of ITMOs toward NDCs.

Article 6.4: the UN crediting mechanism

The second pillar, Article 6.4, is the one that attracts particular attention from the private sector. It establishes a crediting mechanism under UN governance—the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM)—designed to frame the generation and issuance of units resulting from verified emission reductions or removals, as part of international cooperation. The UNFCCC describes this mechanism as a system that “can be used to trade high-quality carbon credits”, often presented as a new step beyond the mechanisms created under the Kyoto Protocol. For companies, Article 6.4 has the potential to become a structuring reference point—more harmonised, more readable, and better aligned with countries’ climate objectives. In return, it implies higher requirements on project traceability and governance, as well as on the methodological compliance of issued units, from impact demonstration through to long-term monitoring and reporting. Many methodologies covering the diversity of carbon projects are currently being developed under the oversight of a UN supervisory body.

Article 6.8: non-market cooperation

The third pillar, Article 6.8, opens a different space: non-market approaches. Here, the goal is not to issue or exchange carbon units, but to enable international cooperation through financing, technology transfer and capacity-building, in support of countries’ implementation of climate objectives (both mitigation and adaptation). The UNFCCC presents this pillar as complementary to the two previous ones, focused on non-market cooperation to deliver NDCs and to support countries—particularly those most affected by climate change—in achieving mitigation and adaptation goals through voluntary public or private finance.

A lens for the private sector

Understanding this three-part structure is essential to avoid a common confusion: not everything under Article 6 is necessarily linked to carbon markets, yet Article 6 provides the most structuring framework for understanding how international cooperation connects to national climate accounting—and, indirectly, to the credibility of instruments used by private actors. As such, the three pillars of Article 6 are a clear marker: climate contribution is entering a phase where requirements are no longer only ethical or voluntary, but structural. Environmental integrity, transparency and accounting consistency are becoming market attributes.

Toward the structuring of international carbon markets

Article 6.4 as a driver of market structuring

Article 6.4, in particular, could accelerate the structuring of international carbon markets around more harmonised rules. Designed first and foremost as an intergovernmental instrument serving countries, it may nonetheless generate units that can later be mobilised by other actors, within regulatory frameworks or for voluntary uses, depending on applicable authorisations and accounting conditions.

Different use scenarios for carbon credits

Under Article 6, a carbon credit is no longer simply a unit that is “bought” or “used”: its pathway depends on how it is recognised and accounted for within the architecture of the Paris Agreement. At the outset, a project generates verified emission reductions or removals. Depending on the host country’s choices, these outcomes can then lead to distinct uses. In a first scenario, units are not transferred internationally under Article 6: they may then be mobilised as a form of climate contribution, provided that their use is described transparently and without claiming attribution of the reduction at the expense of the host country’s national accounting. In a second scenario, if the host country authorises the transfer and accepts the associated conditions, units can become transferable mitigation outcomes. They then fall under an Article 6 logic where accounting consistency is central, notably through corresponding adjustments designed to prevent double counting. The same tonne cannot simultaneously serve the host country’s national pathway and another actor’s claim: its use is defined by the framework that accompanies it. In practice, Article 6 opens a landscape that is both more differentiated and more standardised: some units may circulate as credits recognised within an internationally traceable framework, while others will remain mobilisable through contribution approaches outside of transfers.

A framework still under construction

Beyond these different use scenarios, the intention of the 6.4 mechanism is also to channel finance toward projects capable of delivering climate outcomes, while in some cases strengthening the resilience of ecosystems and local communities. In reality, Article 6.4 is still being operationalised progressively: part of the technical work aims to translate principles into executable modalities able to frame projects and ensure their robustness. For project developers—particularly those working with nature-based solutions—this momentum opens a stronger pathway to recognition, but it also comes with heightened requirements, especially around impact demonstration, monitoring and permanence.

What does this mean for corporate net-zero strategies?

Credibility: carbon credits become a governance decision

Because the operationalisation of Article 6.4 is changing the conditions of credibility and traceability around carbon credits, companies are increasingly encouraged to better articulate their overall climate neutrality strategy. The purchase and use of credits can no longer be treated as a simple act of “offsetting”. It is a structuring decision that directly affects the credibility of a company’s climate trajectory.

Traceability: clarifying the guarantees behind a credit

Concretely, the value of a credit depends not only on the project it finances, but also on the guarantees that surround it: traceability, the rules governing its issuance and monitoring, the conditions under which it can be transferred or claimed, and how it relates to countries’ climate accounting. Article 6 is not a guarantee in itself: it strengthens the framework, but credibility still rests on rigorous diligence—impact demonstration, additionality, permanence, governance and data transparency. This is particularly true for nature-based projects, which carry strong expectations (biodiversity, resilience, adaptation, territorial impacts) alongside heightened evidentiary requirements.

Net zero: reduce first, contribute second

For companies and investment funds, the challenge is now to build climate strategies that can deliver on three promises at once: real transformation (emissions reductions across scopes 1, 2 and 3), the robustness of the instruments mobilised (quality, traceability, governance), and the clarity of disclosed commitments, supported by verifiable evidence. In this context, climate contribution is most meaningful when it is anchored in high-integrity projects, tracked over time and backed by demonstrable outcomes. This is precisely where Reforest’Action’s expertise sits: developing and implementing high-integrity, nature-based carbon sequestration projects, and offering companies concrete solutions to structure and secure their climate contribution in both the short and long term. Through a demanding approach to measurement, traceability and transparency, Reforest’Action enables organisations to rely on robust projects—delivering strong climate and biodiversity outcomes—monitored over time and aligned with the growing strength of international frameworks.

While Article 6 of the Paris Agreement may be seen as a technical topic reserved for negotiators, it is in fact one of the most structuring political frameworks for the decade ahead. As it is progressively operationalised, it raises the level of requirements for economic actors by clarifying the conditions under which international carbon cooperation mechanisms (transfers and crediting) can be mobilised credibly. This evolution—from a still fragmented market to a more standardised and traceable framework—is precisely what makes Article 6 a priority issue for companies and investors. For companies, Article 6 underscores an essential distinction: on the one hand, internal emissions reductions across scopes 1, 2 and 3, which remain the core of a net-zero pathway; on the other, climate contribution, based on complementary financing. In this context, credibility rests less on stated intent than on the ability to document and demonstrate: project quality, unit traceability, conditions of use, accounting consistency and reporting transparency. These requirements directly shape operational choices (project selection criteria, long-term monitoring) as well as external communications, which must make explicit the role of credits within the trajectory and the evidence that supports it. Ultimately, the challenge is no longer only to acquire units, but to anchor them within a clear and verifiable framework, consistent with a net-zero pathway—supporting stronger risk management and more robust investment decisions.