The transformation of agricultural systems represents one of the most powerful levers available to companies to reduce their carbon footprint and strengthen the resilience of their supply chains. As organizations seek to align with science-based decarbonization pathways, the SBTi FLAG framework—specifically dedicated to sectors linked to land use—has emerged as a structuring reference. Understanding its implications and knowing how to apply it in practice has become an essential step for any company dependent on agricultural and forest-based raw materials.

Understanding SBTi FLAG: a structuring framework for supply chains

What are the SBTi and its sector-specific guidance, SBTi FLAG?

The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is today the leading international framework enabling companies to adopt greenhouse gas reduction pathways aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Drawing on IPCC recommendations and a rigorous methodological foundation, the SBTi provides both guidance and validation of corporate climate commitments, ensuring their credibility and alignment with the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

Within this overarching framework, the SBTi FLAG (Forest, Land and Agriculture) sector-specific guidance occupies a distinct position. It translates SBTi principles to the specific context of emissions arising from land use, with particular relevance for sectors such as forest and paper products—including forestry, timber, pulp and paper, and rubber—as well as crop and livestock production, agri-food processing, food distribution, and the tobacco industry. While these sectors are among the most directly concerned, the determining criterion remains the share of FLAG emissions within a company’s overall emissions inventory.

By integrating the biological specificities of these sectors and their unique capacity to sequester carbon, the SBTi FLAG framework provides companies with a dedicated methodological approach, enabling them to define ambitious trajectories that remain grounded in the realities of their value chains.

A framework designed to address the specificities of land-related emissions

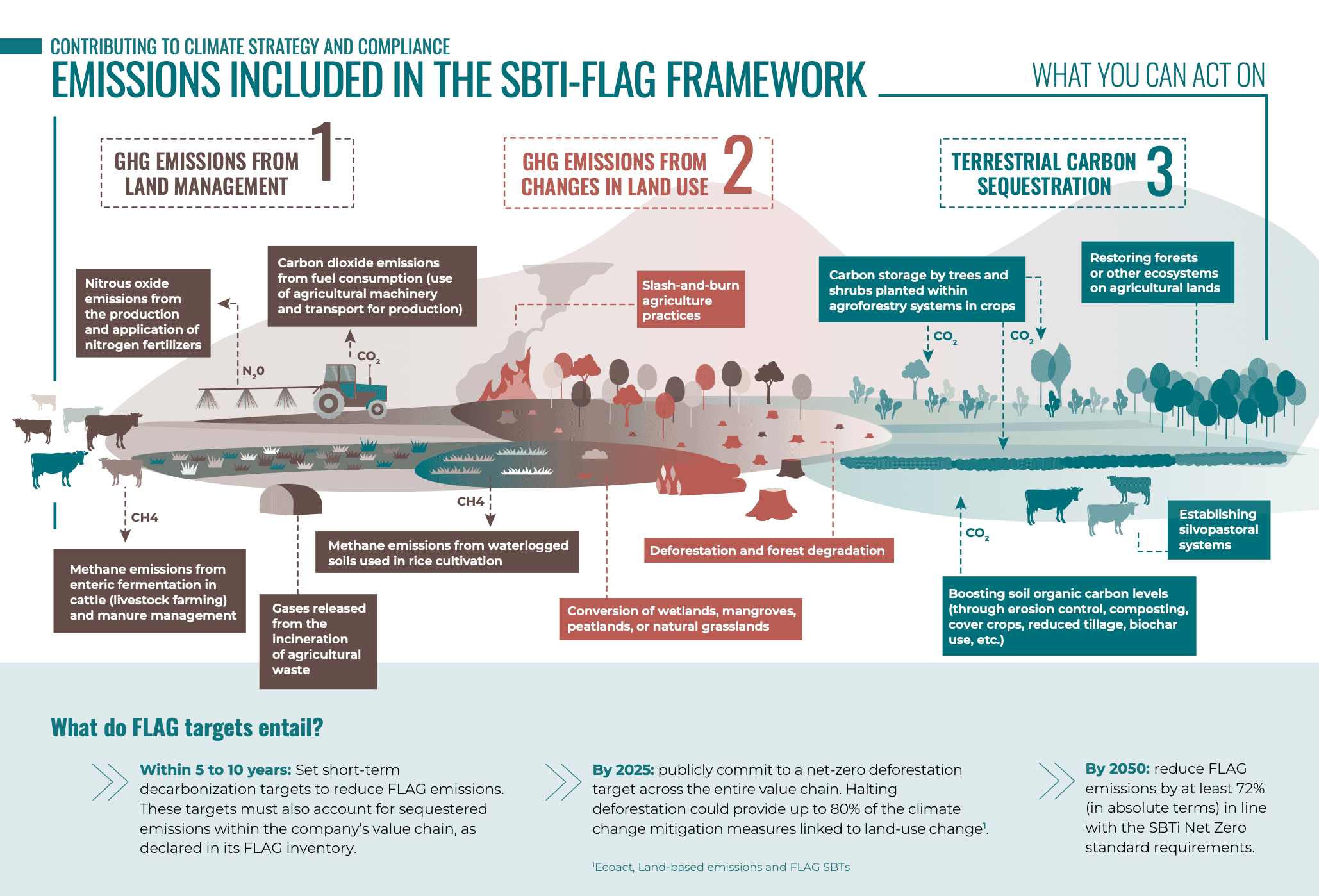

Whereas companies previously focused their carbon reporting primarily on emissions from fossil fuel consumption and land-use change—defined as the conversion of one ecosystem into another through human activity, such as deforestation or the conversion of permanent grasslands into cropland—they must now broaden their analytical scope. Carbon accounting now includes emissions linked to land use itself, understood as the management of land for agricultural production. This broader approach enables a more comprehensive assessment of carbon footprints by accounting for changes in carbon stocks within soils and biomass, whether through depletion or additional storage.

Under the SBTi FLAG framework, organizations whose activities rely on land use are therefore required to set science-based reduction targets over a five- to ten-year time horizon. Moreover, companies operating outside these core sectors, but for which FLAG emissions represent more than 20% of total greenhouse gas emissions, must also establish specific FLAG targets. This requirement ensures comprehensive coverage of land-related impacts, regardless of a company’s primary activity.

Companies whose FLAG emissions account for less than 20% of their total carbon footprint are not required to set SBTi FLAG targets, but may choose to do so voluntarily, provided that the objectives defined are rigorous, measurable, and credible.

A mandatory dual objective: reduce and sequester

The distinctive feature of SBTi FLAG lies in its dual requirement to both reduce absolute emissions and increase carbon sequestration within the value chain. Companies concerned are expected to achieve at least a 30% reduction in FLAG emissions by 2030 under the default pathway—unless a commodity-specific pathway is available—while simultaneously investing in agricultural or ecosystem-based practices that enhance carbon stocks in soils and biomass. This dual requirement reflects the hybrid nature of agriculture as both a source and a sink of carbon, and calls for a profound transformation of practices.

An imperative of permanence and robust monitoring

SBTi FLAG does not merely require results; it also mandates that these results be maintained over time. Sequestration gains may be reversed through changes in practices, soil disturbance, or ecosystem degradation. Companies must therefore commit to robust monitoring, based on measurement, reporting, and verification systems adapted to living systems. This requirement fosters a new type of relationship with producers, grounded in long-term partnership.

Putting SBTi FLAG into practice: key levers for action

Building a robust approach based on measurement, partnerships, and financing

To ensure the credibility of a FLAG trajectory, companies must begin with a detailed understanding of emissions associated with their raw materials and the geography of their sourcing. This mapping exercise helps identify high-risk areas, priority practices for transformation, and opportunities for sequestration. On this basis, co-construction with farmers becomes essential. Shared diagnostics, technical training, innovative contractual arrangements, payments for ecosystem services, and co-financing of agroforestry projects all help create a conducive framework for transition.

SBTi FLAG also requires the implementation of reliable monitoring and tracking systems. Field data, digital tools, and independent verification methods must be mobilized to document changes in practices and ensure the permanence of achieved gains. Finally, the agricultural transition requires financing commensurate with the scale of the challenge. Companies must design risk-sharing mechanisms, economic incentives, and remuneration models capable of encouraging producers to transform their practices sustainably.

Reducing emissions at source through changes in agricultural practices

Reducing emissions within agricultural value chains first requires better control of inputs, both in terms of quantity and type. Nitrogen fertilization is a central issue, not only because of the nitrous oxide emissions it generates in the field, but also due to the high carbon footprint associated with the production of mineral fertilizers, whose industrial processes are particularly energy-intensive. By optimizing nitrogen applications, adapting fertilizer forms, and diversifying crop rotations—especially through the introduction of nitrogen-fixing crops—it is possible to significantly reduce emissions while improving agronomic and economic performance.

In livestock systems, emission reductions also rely on a combination of complementary levers. Adjusting feed rations, improving herd genetics—through the selection of animals that convert feed into useful energy more efficiently, thereby reducing relative methane emissions—and valorizing manure through anaerobic digestion all help lower the climate footprint of livestock production. In all cases, implementing these changes requires close technical support and a durable relationship of trust with producers, which is essential for the effective transformation of practices.

Increasing on-farm carbon storage through agroecological practices

Soil carbon sequestration constitutes a second major pillar of strategies aligned with SBTi FLAG. Agroecological practices—such as permanent soil cover, diversified rotations, reduced tillage, and organic matter inputs—gradually increase soil organic matter and, consequently, stored carbon. Although their effects materialize over several years, these approaches strengthen soil fertility, resilience, and biodiversity.

Agroforestry fully embodies this dynamic by combining two complementary sequestration levers: carbon storage in soils and carbon accumulated in tree biomass. By integrating trees within agricultural plots, these systems enable long-term carbon capture in both aboveground and belowground biomass—including wood, branches, and root systems—while enhancing organic matter flows into the soil. Scientific research increasingly demonstrates that transitioning from conventional agricultural systems to agroforestry significantly enhances overall carbon storage.

A meta-analysis published in Agroforestry Systems, synthesizing several dozen studies across diverse pedoclimatic contexts, highlights a substantial increase in soil organic carbon stocks following the introduction of trees into agricultural plots. These findings confirm that agroforestry contributes durably to biological carbon sequestration, both in soils—particularly in topsoil layers—and in tree biomass, while delivering agronomic, microclimatic, and economic benefits for farms.

Restoring natural ecosystems to preserve carbon sinks

Adopted in 2022 for application as of 31 December 2026, the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) requires companies to demonstrate, on a product-by-product basis, the absence of deforestation after 31 December 2020. In this context, strengthening traceability, integrating strict purchasing criteria, and contractualizing sustainable management practices with suppliers becomes indispensable. These approaches may be complemented by programs to restore degraded agricultural or forest landscapes within sourcing territories, contributing both to carbon sequestration and regulatory compliance.

For many companies, protecting ecosystems located within or upstream of their value chains therefore represents a major impact lever, particularly when sourcing raw materials from regions exposed to deforestation or land conversion risks. By reorienting sourcing strategies toward land preservation and sustainable ecosystem management, companies can simultaneously meet the requirements of the EUDR and SBTi FLAG, while reinforcing the environmental and social resilience of the territories on which their activities depend.

As deforestation remains one of the primary sources of FLAG emissions, recent evolutions of the SBTi FLAG framework further clarify corporate commitments in this area. Companies now have up to two years after the validation of their FLAG targets—and no later than 31 December 2030—to achieve deforestation-free supply chains. In addition, commitments must cover the seven commodities defined by the EUDR—cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, and timber—whenever each represents at least 5% of a company’s gross FLAG emissions. This evolution, opened for consultation at the end of 2024, strengthens coherence between SBTi FLAG and European regulatory requirements, facilitating convergence across compliance systems.

Reforest’Action supports companies in the agricultural transition

Reforest’Action provides companies with tailored support to integrate regenerative agriculture directly into their value chains. Drawing on more than 15 years of expertise in agroforestry, we design projects adapted to local contexts and to corporate strategic objectives, whether to secure supplies, reduce carbon footprints, or enhance land resilience. Our approach unfolds in four key stages—feasibility assessment, project engineering, implementation, and long-term monitoring—to ensure tangible and lasting results.

By combining soil restoration, agroecological practices, agroforestry, ecological monitoring, and support for local communities, our approach delivers multiple benefits: carbon storage, enhanced biodiversity, improved soil health, water quality protection, yield security, and positive socio-economic impacts. For companies, this represents not only a concrete response to SBTi FLAG requirements, but also a structured contribution to the environmental and social sustainability of their production chains.

Meeting SBTi FLAG requirements is not merely a matter of adopting an additional methodology. It represents a paradigm shift that entails a profound transformation of agricultural practices, commercial relationships, and territorial investments. By acting simultaneously on emission reductions, biological carbon sequestration, and ecosystem restoration, companies can not only meet scientific criteria, but also strengthen the resilience of their supply chains and create a lasting competitive advantage. SBTi FLAG thus emerges as a major opportunity to anchor climate action at the very heart of agricultural landscapes and contribute to the regeneration of living systems.

Are you a company looking to evolve practices related to the production of your raw materials? Our experts are available to discuss your challenges and support your strategic thinking. Contact us.

RESOURCES

White paper: Regenerative agriculture. This white paper provides a comprehensive overview of why initiating an agroecological transition is essential to ensure the long-term sustainability of your activities and create value for your company. Discover why and how to implement a regenerative agriculture project that will help you achieve your SBTi FLAG objectives.